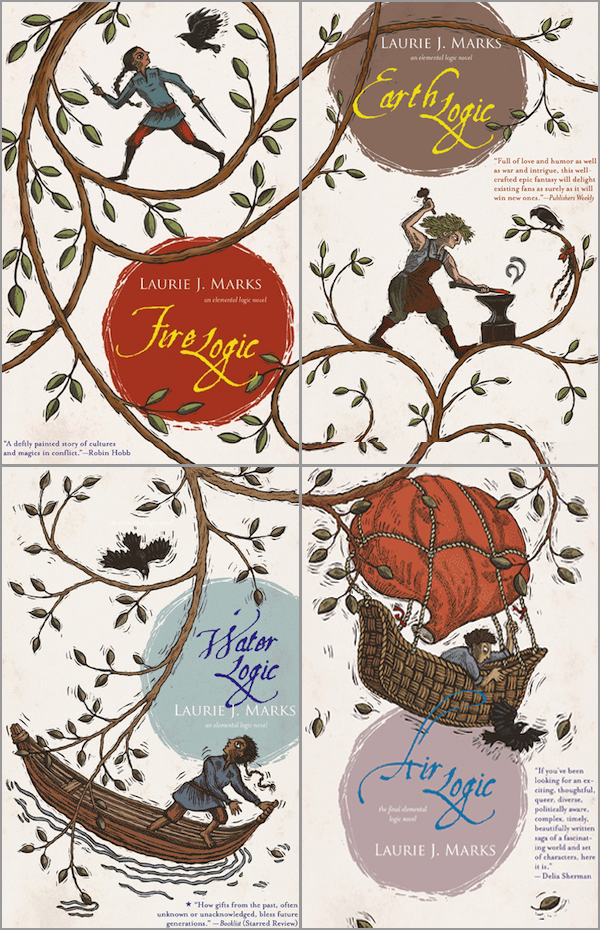

Time and water share characteristics, moving in currents, eddies, flows—and that fluid, continual circulation animates the third novel in Marks’s Elemental Logic series. In a similar vein to its namesake, Water Logic is a subtler book than the crackling Fire Logic, yet more capriciously changeable than Earth Logic. It might seem odd to call this novel subtle, considering that its central conceit is an upheaval in the timeline that drags Zanja two hundred years into Shaftal’s past, but its arguments are by design less concretely executed and more illustrated as a dance of ideas.

With the war finally ended but resentments and conflict still festering, the dilemma facing the new combined governance of Shaftal is no longer political first and cultural second. There’s a political center in place, but its reach to change the social order in far-flung, significant ways relies less on given law and more on the ability to conceptualize and spread a narrative of change. What’s needed are stories for a new society, a path that stretches past the door Medric opened with his A History of My Father’s People. In that sense, Water Logic is as philosophical as the prior books were political, a slight but dynamic reorganization of narrative priorities.

Time and ethics, ethics and time. Faced with a seemingly-insurmountable problem, intractable differences across cultures and the justified resentment of victims toward their oppressors, Karis and her chosen family must adapt their priorities and their approach to the great work of rebuilding a nation. In this novel, Marks constructs an elaborate and tense plot full of trips through time, assassination attempts, mutineers, and interpersonal conflict, while simultaneously illustrating a rich, humane argument about the nature of incremental social change through the struggles of her characters.

As with the Elemental Logic series as a whole, stories are central, here. Marks’s novels are metafictional in a sideways sense: they’re stories that make an argument, and they do so by embedding other stories that illustrate that story. The layers allow for both an engaging plot and significant artistic work to occur simultaneously. It’s telling by way of showing—letting the work illustrate the point. Three characters in particular, Zanja, Clement, and Seth, provide points of philosophical and narrative focus in their pivotal work between the present, past, and future. As individuals from three distinct cultures in contrast to one another, they also provide the example of how it is possible to create unity without erasing or ignoring individual difference.

Trapped in the past and acting on instinct to change things that must be changed without entirely disrupting the timeline that leads to the future, Zanja offers the text’s most direct ethical statement alongside the great quandary it presents:

…[she] found herself muttering the ancient axiom on which was based the ideology of the Paladins: “Evil may enter the world, but it will not enter through me.” To Zanja this goal now seemed not only simpleminded, but unachievable. No person could ever know the ultimate result of his or her actions, and no person could know whether that results might be good or evil or something else entirely.

For Zanja, the question of how to behave ethically runs up against the terror or not being sure of the consequences of her actions—literalized by her position as a potentially disruptive force in the actual past. The metaphor of a small action leading to big changes is made real by the nature of her time-travel. Unlike most people, who will never see the longest reach of their actions, she actually might—and it makes action that much more difficult.

Buy the Book

Water Logic

In contrast to the literal nature of Zanja’s ethical quandary, Clement’s education in becoming Shaftali is in large part conducted through readings on ethics—readings which frustrate her immensely, as she frequently laments that the writers and her Paladin debate partners don’t just provide her with answers to the questions they pose. In her debate with Saleen, he presents Clement with an axiom, “War is a failure of philosophy.” She responds, “Do you mean that philosophy can’t account for war? Or that war occurred because of people failing to think properly?”—and his answer is, “Oh, we are still arguing about that.”

Clement, as a Sainnite soldier-cum-general, has been struggling to conceptualize a world outside of rote orders and response, actions taken without consideration for their outcomes. If force is the only answer, everything looks like a war. She must learn, and teach her people, the possibilities that exist outside of that answer and in the meantime decide when force is still necessary to preserve the fragile peace they’re in the process of constructing. Clement’s ethical dilemma is the grey area between right and wrong, the power of trusting one’s individual instincts while also learning how to expand on those instincts in order to encompass better responses.

Seth, erstwhile cow doctor and Clement’s sometimes-lover, provides another individual and living example of the sort of gradual changes that lead to major shifts. The private conversation she has with Norina about her earth-logic insights, pushed a little to directness by hints of fire and air, is a guidebook and an emotional revelation all at once. Norina notes that Seth is preternaturally good at sorting the small things that can be influenced, fixed, settled. Without being paralyzed by indecision or the scope of the problems all stacked one atop another, she acts, fixing the things she can put hands on to fix and relying on a knock-on effect to settle the rest. What she cannot fix, she sets aside for another time or another set of hands. And it is she who, at the end of the novel, provides another philosophical answer to the problem of war, only to herself, only in the silence of her bed. She thinks, “peace […] is not merely an absence of war. It is all the things war displaces, the things war makes not merely unachievable, but unimaginable. Only peace makes peace possible.” In other words: it’s a leap of faith, and it is the small actions that seem no longer possible to imagine but must be done regardless.

To make peace in a living world, you’ve got to think bigger than the present moment and its constrictions. Do the impossible that is, in fact, possible. All three characters, out of their individual experiences and cultures, come to the philosophical argument Marks makes through direct and indirect means. Patterns bigger than all of us are shaped by our actions, and the past is as important as the future. Ethics is a necessary discipline because it allows us to conceptualize present actions in their scope—by which I mean that despite Zanja’s observation that one can never know the effect an action will have ahead of time, that doesn’t mean it’s impossible to act well. Instead, the consideration of how the small affects the large might allow a person to remember that acting ethically from moment to moment is the only way to ensure, as much as possible, that evil does not enter through us into the future.

It’s an ongoing work, at all moments and all times, to be a good person, to behave ethically in the present moment, and to believe in the potential for a better future. In Water Logic, part of the work of unification is about finding areas of common ground without either homogenizing or conquering. Zanja’s trip to the past reveals a Shaftal that is not as much a home-and-hearth as she expected; her people are treated as outsiders without respect and it infuriates her. It takes work to be welcoming and to create space without erasing difference, to be equitable. That work happens over decades in Marks’s novels. Damon, the Sainnite soldier who travels with Seth, is able to connect with a Shaftali lover over a shared care of flowers, and as small as that may seem, it is a bridge built over the turbulent waters of their cultural differences.

Water Logic is also, lest I make it sound entirely like an allegorical treatise, a book about women’s partnerships—Seth and Clement, Zanja and Karis. Marks gorgeously explores the human difficulties of partnership through these couples and the familial structure that has grown up around them, a queer communal life and governance, without making it seem too easy. Zanja and Karis are in regular conflict; it’s their opposite natures, one stolid and one ever-travelling, but each book has included a pivotal moment of reunion featuring tender but passionate physical intimacy. Their relationship is loving and it’s also work. Seth and Clement also have to do the work—but it’s their work, struggling with their personal flaws and the politics that have kept them separated though they don’t wish to be. The narrative of this book is tighter in its focus and timeframe, so we’ve seen less of Medric and Emil (and Garland), but what we do see also matches—they work to harmonize, they work to understand one another and share the burdens of a familial life; they adapt.

As it is on the small, personal scale, so it shall be on the biggest stages. Not to be obvious, here, but Marks has managed to deftly illustrated the connection between the personal and the political. Relationships take work, ethics takes work, and the efforts we make one day at a time ripple far into the future. It’s a great work, and it’s never done, but our protagonists have conceptualized it well. One person, one action, one moment have the ability to fix even the largest problems—so long as they’re stacked up over and over again with consistency and real willful effort. Hope is, once again, a discipline. The literal physical embodiment of continuity, the lexicon that proves the first Shaftali were refugees from Sainna who arrived in a land then populated entirely by the border tribes, has been found through time at the end of Water Logic. The revelation that the people who consider themselves Shaftali were once themselves immigrants to the land they consider their own now also reveals the complex histories of colonialism that they themselves have participated in as aggressors.

It remains for the final book, Air Logic, to put that knowledge of the past to use for the express purpose of radical change.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.